In 1895, the cinematic journey embarked upon a 32-year odyssey marked by a conspicuous absence of dialogue. Despite the discovery of the camera and the crafting of exquisite films through advanced editing techniques, the sound remained conspicuously detached from this cinematic evolution. Visionaries such as Lumiere and Edison attempted various methods to incorporate sound into films, yet unfortunately, all endeavors proved futile. The period spanning these 32 years, during which dialogues were conveyed through intertitles, is referred to as the “silent film era.”

Following this extensive era, Warner Bros., in 1927, unveiled a groundbreaking cinematic revolution with the introduction of the first synchronized sound film, “The Jazz Singer,” utilizing the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. The advent of sound precipitated a comprehensive transformation in the realm of cinema. The iconic and tumultuous transitional phase depicted in films like “Babylon” (2023) and “The Artist” (2012) had begun. As actors ill-suited for sound cinema distanced themselves from the industry, studios found themselves compelled to revamp their facilities to align with this innovative system, giving rise to the Studio System.

The pivotal question arises: Were silent films truly silent? Was there an absolute absence of sound within these films? The simplest answer to this query is affirmative. Films, regrettably, were genuinely silent. However, this does not imply that audiences experienced these films in absolute silence. On the contrary, the silent film era was, paradoxically, more cacophonous than the present, undergoing a tumultuous transformation.

Music in Cinema

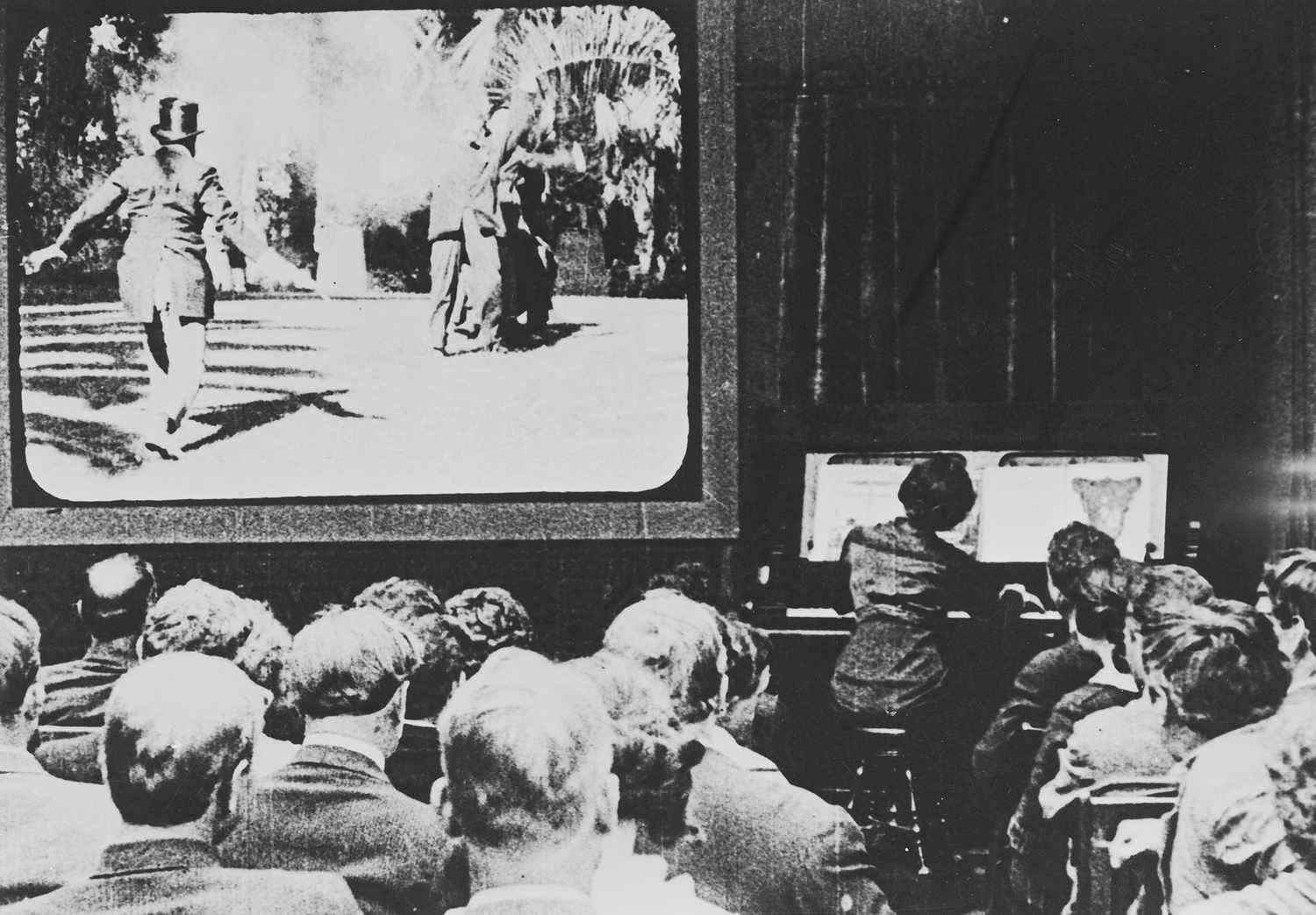

During the nascent years of cinema, films were showcased in theaters known as Nickelodeons in the United States. For a mere 5 cents, one could watch all the films shown throughout the day. Even before a spectator entered the Nickelodeon, they could hear the ambient noise emanating from within. Upon opening the door and stepping inside, the first sight encountered would be an individual or individuals in a corner playing music and a B&W 16mm film projected onto the big screen.

While films were inherently silent, they were never presented in complete silence. There was always accompanying music, sound effects, or a narrator providing support to the films. In the early days, films were exclusively presented with musical accompaniment, but this supportive role gradually evolved into an industry of its own. In a classical film screening, a pianist or, at the very least, a system for transmitting music would accompany the film. As time progressed, being a pianist or an organist transformed into a profession. Some theaters prioritized the music accompanying films, while others neglected its importance, leading to instances of inappropriate music or inexperienced pianists.

Music was an indispensable component of the silent film era. Films always featured music that would complement and enhance the emotions portrayed in the film. In large theaters or premieres of significant films, orchestras sometimes performed concerts during the screening. Our available information indicates that meticulous planning was put into the organization of music played during the film.

Moreover, as time advanced, sound began to be employed not only to add depth to films but also to incorporate suitable sound effects into scenes.

In the 1910s, as cinema theaters expanded, so did the musical accompaniment. A dedicated section for musicians was created in one corner of the theaters. Typically, this specialized section accommodated three individuals: a melody instrumentalist, a pianist, and a percussionist.

Film Scores

The 1910s marked a pivotal era when music seamlessly became an integral part of cinema. Initially merely an accompaniment, music evolved into an indispensable component of films, playing a substantial role in their production. Films began to take shape based on the music to be played, and the first examples of film music emerged during this period. As the design of original music for films became prevalent, notable composers such as William Axt, Giuseppe Becce, Carli Elinor, Louis Levy, Hans May, Erno Rapée, Hugo Riesenfeld, and Marc Roland came into prominence.

While film music had its origins in the 1910s and 1920s, it took time for its true value to be recognized. This delay was attributed to the fledgling state of the cinema industry, distribution challenges, and the abundance of films, making it seemingly impractical and cost-prohibitive to commission music for them. Moreover, there was a limited number of individuals capable of playing and producing such music. Some significant film scores from this era include:

The Battle Cry of Peace (J. Stuart Blackton, 1915; S. L. Rothapfel, with Ivan Rudisill and S. M. Berg), Joan the Woman (Cecil B. DeMille, 1916; William Furst), Civilization (Thomas Ince, 1917; Victor Schertzinger), Where the Pavement Ends (Rex Ingram, 1922; Luz), The Big Parade (Vidor, 1925; Axt and David Mendoza), Beau Geste (Herbert Brenon, 1926; Riesenfeld), Wings (William Wellman, 1927; J. S. Zamecnik); and four films by D. W. Griffith: Hearts of the World (1917, Elinor), The Greatest Question (1919, Pesce), Broken Blossoms (1919, Louis Gottschalk), Way down East (1920, Louis Silvers and William F. Peters).

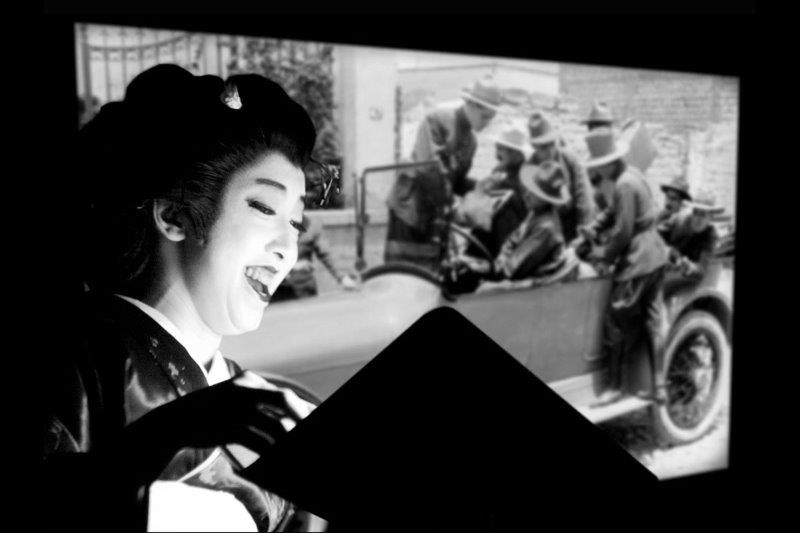

Benshi Culture

While America and Europe primarily presented films with musical accompaniment, Japan followed a considerably different approach. A person known as a “Benshi” would stand beside the screen during the film, narrating the events to the audience. For those familiar with silent films, understanding precisely what is happening on-screen can be quite challenging. The Japanese devised a solution to this by introducing a narrator. The Benshi would sometimes appear before the film, during it, or at its conclusion, conveying the events of the film to the audience.

In the early days of Japanese films, the Benshi served as a character who briefly summarized the on-screen events. However, as films evolved into more complex narratives, Benshi began to narrate scenes in detail, accompanied by Japanese music. Over time, the number of Benshi increased, with multiple individuals providing voices for characters in the film. Similar to musicians in Hollywood, Benshi narrated the film in a way that enhanced its impact. Eventually, Benshi, with captivating storytelling and pleasing voices, became an integral part of films. Musei Tokugawa is recognized as one of the era’s most prominent Benshi. Benshis even started playing a significant role in the production of films.

The narration by Benshi played a substantial role during the Japanese silent film era. Their storytelling skills were a pivotal factor that both heightened and diminished the impact of films. Benshi, especially those attempting to convey the emotions in the film, sometimes went beyond the censorship imposed by the state, describing kissing scenes and other moments in their own styles. Although Japan initially sought to keep cinema entirely local, they eventually had to open up to foreign films. Some theaters, especially those catering to intellectual audiences, showed films with subtitles, but in certain venues, Benshi translated films for the audience.

In 1927, 180 of the 6,818 Benshi were women. The presence of women among this high number is quite surprising, particularly when considering that, during the silent era of Japanese films, women were thought to be played by men. Thus, having women as Benshi was a fascinating phenomenon.

1927 and Beyond

With the advent of sound in cinema in 1927, silent films continued for a while. Although music continued to accompany films, Benshi gradually faded away from theaters. Despite the Benshi culture persisting until the mid-1930s, it succumbed to the passage of time, transforming into a nostalgic relic. For those interested, I recommend the 1995 film Picture Bride, which portrays the life of a Benshi.

Yes, during the silent film era, films were genuinely silent due to technological limitations. When we refer to silence, we generally mean the absence of dialogue. However, films were never watched in complete silence; music always accompanied them. When one visits a Nickelodeon, one experiences films accompanied by beautiful music, enhancing the pleasure derived from the cinematic experience.

Nowadays, having music played during a film is an activity that astonishes everyone, evolving into an event for which cinephiles are willing to pay. I am one of those individuals. Particularly, I am prepared to pay a considerable amount to watch The Lord of the Rings with a live concert accompaniment.

Sources and Further Information

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey. “The Oxford History of World Cinema,” Oxford University Press (1999)

- Teksoy, Rekin. “Rekin Teksoy’un Sinema Tarihi,” Oğlak Yayınları (2014)

- Scognamillo, Giovanni. “Amerikan Sineması,” Alternatif Üniversite (1994)

- Robb, Brian J.. “Silent Cinema,” Oldcastle Books (2007)

- Chansel, Dominique. “Europe On-Screen: Cinema and the Teaching of History,” Council of Europe (2010)

- Cousins, Mark. “The Story of Film: An Odyssey” (2011)