When you open a book on cinema history, the first three names you encounter will be the Lumiere brothers, Georges Melies, and D.W. Griffith. While the Lumieres introduced the invention of cinema, Georges Melies added narrative to it, exploring all possibilities of the medium through his storytelling and effects. On the other hand, D.W. Griffith is the architect of the modern rules of this new art form, laying the foundations that we still use today.

Although Griffith is predominantly remembered for a single film, which we will delve into later, he was much more than just a filmmaker. Revered as a father of film, Griffith was one of the few individuals who taught filmmaking to the masses. His signature works encompass the building blocks of the industry, which continue to shape and evolve the sector today.

In the context of contemporary political sensibilities, merely mentioning figures like Griffith is almost deemed taboo, considering his racist inclinations. However, discussing both his art and life requires courage. It’s crucial to understand the valid criticisms directed towards him and the motivating factors behind his controversial works. Recognizing that his contribution extends beyond a single film and acknowledging his impact on cinema is imperative.

Early Years

David Llewelyn Wark Griffith was born in La Grange, Kentucky, just outside Louisville, as one of seven siblings. His father, Colonel Jacob Wark Griffith, known as “Roaring Jake,” was a hero of the American Civil War. In David’s life, the influence of his father was profound.

Colonel Griffith had a great love for stories. Hence, he introduced his son to the works of Shakespeare, Poe, Dickens, and Longfellow, ensuring his education. Moreover, it was his father who inspired David to pursue a career in directing. Colonel Jacob Wark Griffith occasionally took his son to the Magic Lantern, introducing him to primitive cinema.

Yet, this same father, who laid the foundation for his son, would later be remembered as one of history’s greatest racists. Colonel Griffith molded his son with the traditions of Southern culture. The stories he told would leave an indelible mark on his son’s mind, inspiring him to transform these tales into films throughout his life.

At the tender age of 10, Griffith lost the father he would later profess to love most. His father’s death marked a pivotal moment, altering the course of his life. Before his passing, the family farm was struggling. Though the Civil War had ended by the time David was born, the aftermath had left America, reborn but fractured, shaking the foundations of many families. With the abolition of slavery came significant hardships, especially in the South. David attributed all the farm’s troubles not to his father, but to the Civil War, holding it responsible for their plight.

Love for Art

Upon his father’s passing, the family relocated to Louisville. Griffith, forsaking his education, sought to support the family by taking on various jobs. He learned everything he could from his sister, who was a teacher. However, Griffith’s heart was always set on creating art. Thus, he gravitated toward the theatre. He took on minor roles in some plays and worked backstage as a prop assistant. While his mother wished for him to become a preacher rather than an actor, Griffith’s passion for art prevailed. Ignoring his mother’s wishes, he abandoned everything to pursue his desire to become a writer and moved to New York.

In pursuit of his dream of becoming a director, Griffith approached Edison’s company, intending to sell them a screenplay, but found himself cast as an actor instead. Although he engaged in acting for a while, it was his experience directing “The Adventures of Dollie,” starring his wife Linda Arvidson, that completely changed his perspective. Griffith wasn’t particularly fond of his first film. But the overwhelming response from the audience convinced him that acting was not his path. Failing to achieve what he desired from Edison, Griffith turned to Biograph, where he also acted for a period. However, Biograph was facing financial difficulties at the time, and with a shortage of directors, the company, upon the recommendation of cameraman Arthur Marvin, offered Griffith a six-month directorial contract. David accepted on the condition that if he failed, he would have the opportunity to return to acting. Yet, Griffith never looked back to acting again, as he achieved success with his very first film.

Years in Biograph

Griffith’s years at Biograph were remarkably productive. Over the span of five years, the director crafted more than 400 short films, honing his directing skills while also making his actresses famous alongside him. Working with various genres from drama to comedy, horror to action, Griffith frequently collaborated with the likes of the Gish sisters, Blanche Sweet, Mary Pickford, and his wife, Linda Arvidson. So much so that the Gish sisters and Blanche Sweet emphasized their strong bond with David by stating, “We were not working for Biograph, but for David.“

In fact, when Griffith left Biograph after five years, his actors departed with him.

In his films at Biograph, Griffith delved into specific themes he believed would captivate the audience: women awaiting the return of their loved ones from distant seas, action-packed scenes on train tracks, burglars attempting forced entries into homes, civil war stories, and love triangles. Women always held a central place in his narratives. Even if there were children in his films, they were invariably girls. In his movies, women often supported each other, consoling one another in times of distress.

In Griffith’s films, women sometimes portrayed characters awaiting rescue, while at other times, they took on the role of secret heroes fighting alongside men.

They were characters who sacrificed their lives, protecting their loved ones until the end, battling against thieves, and facing death alongside their beloved.

However, in Griffith’s films, a happy ending was not always the only option. Death was a recurring theme in Griffith’s films, reflecting the realities of the time. His films featured infants succumbing to illness, women dying of longing, wives losing their husbands, and men committing suicide.

Griffith shot two films a week for Biograph. The secret to his ability to produce over 400 films in five years lay in his emphasis on rehearsal and the fact that indoor scenes were shot in Biograph’s studios. It’s possible to spot the company’s logo in the background of many Biograph films. Sometimes, the films were set in the same locations. The shots were mostly stationary, but what set Griffith apart was when he moved his camera.

During Griffith’s era of filmmaking, close-up shots were not commonly preferred. Film owners argued that they paid the actors for the entire body, not just half. However, Griffith frequently utilized close-ups and became quite adept at it. He was particularly successful in conveying the emotions of his characters.

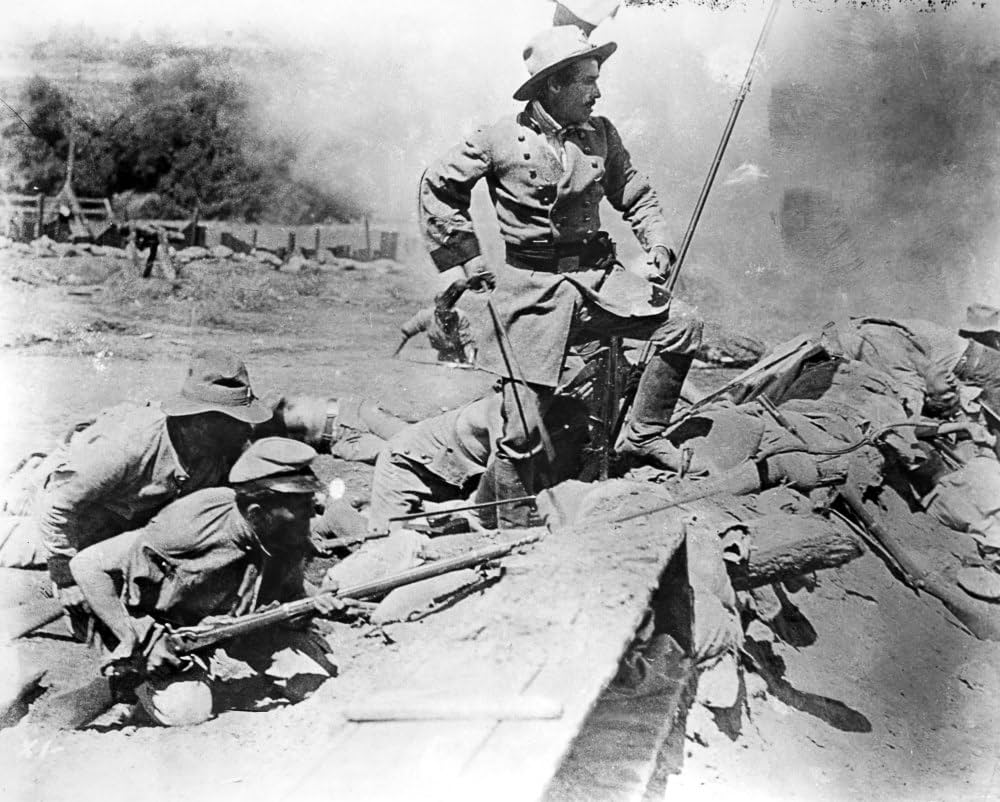

Griffith did not appreciate the popular style of the time, the trick films produced by Georges Melies. He preferred a simpler narrative style, often drawing inspiration from his own childhood experiences. Rural settings, reminiscent of his upbringing, were frequently featured in his films. Griffith believed that the cinema camera could bring about social change. Therefore, he often depicted themes of war, inspired by stories he heard from his father. Griffith himself would orchestrate war scenes in his films, demonstrating his prowess in creating action. The train chase scenes in his 1912 films “A Beast at Bay” and “The Girl and Her Trust” were no different from those seen in modern “Mission Impossible” movies.

In the early 1900s, actors’ names were not written on film posters, a fact that pleased Lillian Gish’s mother. Acting, especially for women, was not considered a respectable profession. Cinema was a burgeoning industry and was not yet taken seriously. Even Griffith’s name did not appear in the films he directed for Biograph. And the company saved money by not listing actors’ names on posters. However, the women in Griffith’s films began to gain fame, and audiences started to inquire about their identities. They became known colloquially as the “Biograph girls.”

As their fame grew, their names began to appear on posters, signaling the transformation of acting into a serious profession.

After spending five years with Biograph, Griffith left the company. Having directed over 400 short films, he now aimed to make feature-length films. During this period, Thomas H. Ince was making long action films, while Italy was producing feature-length historical films. Griffith also aspired to make feature-length films like them. Although he had already exceeded the 30-minute mark in “The Massacre” (1912) and surpassed 50 minutes in “Judith of Bethulia” and “The Avenging Conscience” (1914), he felt it wasn’t enough. Biograph, however, was interested in investing in short films. Thus, Griffith declared his independence, taking his actresses with him to create a legendary film.

The Birth of a Nation

After Biograph, Griffith embarked on his most ambitious project, “The Birth of a Nation.” Nearly $110,000 was spent on the film, which turned into a nine-week endeavor. Even the rehearsals for the film lasted six weeks. However, Griffith was resolute in his intentions. He aimed to create a grandiose film. Although he succeeded in his vision, the foundations upon which he built his film were so flawed that they eventually toppled over him.

First, let’s discuss the positives of the film.

In “The Birth of a Nation,” Griffith tells the story of two different families, one from the South and one from the North, simultaneously, through a parallel narrative. At the time, this dual journey was a novelty. Focused on the Civil War, depicting the conflict between families supporting two different sides, the film featured many unprecedented techniques and scenes.

With its parallel narrative structure, action scenes on horseback, dramatic close-ups, deep focus shots, special effects, and its relatively long runtime of three hours, “The Birth of a Nation” introduced numerous innovations. However, the film was not just special because of these innovations. Griffith was not the first to discover them. He simply mixed them all into one, creating what many consider to be the first example of modern cinema. With its exposition, rising action, and resolution, encompassing all the techniques still used in cinema today, it was the first modern film to captivate audiences for hours with its fluctuating tempo. In today’s terms, it was the first blockbuster in history. It featured unprecedentedly intense battle scenes. Excluding a brief family prayer scene lasting five seconds, it had a battle sequence lasting over ten minutes.

After “The Birth of a Nation,” cinema was never the same. Even those within the same industry as Griffith learned a great deal from him and his films. His theories inspired Russian filmmakers who would later shape the future of cinema. Eisenstein, who would later revolutionize cinema with “Battleship Potemkin,” drew inspiration from “The Birth of a Nation.” Similarly, Abel Gance, one of France’s legendary directors, was also an admirer of Griffith.

Griffith dedicated almost his entire being to this film. Midway through production, when the budget was depleted, Griffith, refusing financial aid from the Gish sisters, managed to finish the film somehow with funds raised from the community. According to Lillian Gish’s account, no matter how much money was spent on the film, it always faced budgetary constraints, resulting in most of the shots, including the battle scenes, being done in a single take.

And, as always, the secret to his success was rehearsal.

When Griffith attempted to release the film, he encountered problems due to its 12-reel length. Many cinemas refused to screen it. In response, Griffith showcased the film only in serious cinemas, on an unprecedented scale, accompanied by massive orchestras. In an era when tickets were sold for cents, the film debuted at an astronomical $2, and despite exorbitant ticket prices and all the criticism it received, it achieved unprecedented box office success, propelling Louis B. Mayer onto the rich list.

Racism

Now, let’s examine the other side of the coin.

Despite Griffith’s reluctance to admit it, the film, adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel “The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan,” was an extreme portrayal of racism. Consisting of two parts, “The Birth of a Nation” attempts to stay faithful to the real history of the Civil War in the first part, but the second part is embellished with Thomas Dixon Jr.’s fantastical visions of black people. The blacks depicted in the second part are portrayed as unrealistic, deriving power from the North to oppress the South, perverse-minded individuals, cheating while voting, taking off their shoes and consuming alcohol in Congress, and barbarians incapable of bearing the rights granted to them. Even more ironically, newly liberated blacks are depicted as being able to attain positions of power and using them to oppress whites. Blacks even deny whites the right to vote through oppression. At the film’s end, whites retaliate by doing the same to them.

The film not only depicts a black-white conflict but also portrays segregation within the black community itself. The Cameron family’s maid doesn’t hesitate to insult the emancipated black who comes to their house. Later in the story, freedom fighters attempt to punish blacks who don’t vote for the Union by whipping them.

One of the most criticized aspects of the film is that many of the actors playing black characters were not actually black. In the film, all black characters who have significant roles on camera, or rather, who would interact with a white actor, are played by whites with painted faces. Interestingly, the maid of the Cameron family is not only played by a white actor but also clearly a man.

Whitewashing black characters was not unique to “The Birth of a Nation.” Griffith had done it before. In his 1910 film “The House with Closed Shutters” and his 1911 films “The Rose of Kentucky” and “His Trust,” there are characters with blackened faces. During times when blacks struggled to find roles on screen, potential black characters were played by whites with painted faces. Griffith continued this approach in his later film “Dream Streets.”

However, the claim that all black characters in the film were played by whites is inaccurate. Upon careful examination, it’s possible to see many black characters in the film. One of these characters, Madame Sul-Te-Wan, who would even attend Griffith’s funeral and whose children loved Griffith like a father, is among them. Madame, who was among those who criticized the film after its release, was fired by the company for her stance. However, with Griffith’s intervention, Madame Sul-Te-Wan got her job back and, this time, became a contracted actress, appearing in Griffith’s next film, “Intolerance.”

However, the sole focal point that ignited debates about the film was, of course, the Ku Klux Klan.

The KKK was portrayed as the film’s hero, greeted with applause by the South as saviors. Griffith attempted to depict the KKK, coming to rescue the struggling South, as an independent entity, but by having Ben Cameron don a mask and involve his family in the production of the attire, he essentially equated the South with the KKK itself. While the South tried to convey that its rights were taken away and it fell on hard times, intentionally or unintentionally, it drew the entire South into the realm of racism by making it a part of the KKK.

Contrary to popular belief, the KKK did not make its first appearance in Griffith’s films. In the 1911 film “The Rose of Kentucky,” KKK characters were seen but portrayed as traitors to the town this time. Some claim that the newcomers were merely KKK-masked bandits, while others argue that the townspeople were only engaged in a power struggle within the KKK.

Griffith’s controversial film received approval even from the White House. President Woodrow Wilson personally summoned Griffith and expressed his admiration for the film. Like a new civil war, the film divided the entire country again. While the film was banned in cinemas in many parts of the country, in many other places, cinemas were requesting the extended cut. However, the intensity of the objections was high. People took to the streets to protest against the film. William Walker recalls watching the film in a cinema for black people in 1916 and says that some people were sobbing uncontrollably after watching it.

D. W. Griffith never admitted to being racist at any point in his life. His defense was that he adapted to the circumstances. His beloved actress, Lillian Gish, always defended him.

However, when interpreted in light of the film’s trajectory, what Lillian Gish meant actually has a negative rather than a positive connotation; the quote refers to the oppression that blacks would impose on the South.

Although the Civil War had ended and slavery had been abolished, blacks remained second-class citizens. They were scorned and marginalized. The damage the South suffered due to the abolition of slavery further fueled the hatred of blacks among the people. In such a period, the success of a film that depicted blacks as monsters would not be surprising. Griffith’s attempt to venture into such an aggressive film, which he had never tried before, followed by his denial of all accusations and attempts to respond in his own way, gives rise to many contradictions.

Intolerance

Griffith was uncomfortable with the racist accusations attributed to him. He felt the need to respond. He wanted to give this response through filmmaking. “Intolerance,” released in 1916, may perhaps be his best film, contrary to what many may think. It is a magnificent film that challenges the colossal sets established by the 1914 masterpiece “Cabiria” that impressed and captivated audiences.

“Intolerance” is like a journey through time, attempting to depict the grandeur of bygone eras with great splendor. The entire film was designed based on 19th-century paintings. The budget for the film exceeded that of “The Birth of a Nation.” People waking up in the city where it was shot would see a towering cityscape when they looked out of their windows every morning. The sets were so immense that they could be seen from everywhere.

In the film, Griffith tells four different stories: Babylon in 539 BC, the crucifixion of Jesus, the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572, and an American story in 1914. At the core of all these stories is, as always, a downfall. Griffith seeks to convey intolerance and its consequences using his method, the camera, which is a social tool. And in doing so, he introduces many innovations, just like he did in “The Birth of a Nation.”

“Intolerance” particularly depicts unprecedented brutality in the sequences set in Babylon. Severed heads, innocent deaths, massive machines spewing fire—everything unfolds within awe-inspiring colossal sets. Griffith introduces innovations in this film by employing pan and dolly movements, previously seen in “Quo Vadis” and “Cabiria.” He also uses the tilt movement for the first time in this film.

What sets Griffith’s “Intolerance” apart from its reference points, “Quo Vadis” and “Cabiria,” is his approach to the film. While “Cabiria” and “Quo Vadis” do not include a single close-up shot, Griffith adorns the film with powerful and impactful close-ups like never before.

However, what truly distinguishes the film is Griffith’s approach to editing. Instead of narrating the four different stories separately, Griffith breaks down the narratives into fragments, especially accelerating the transitions in the finale, creating an unprecedented structure.

First, he shows Cyrus heading towards the destruction of Babylon. A few seconds later, he transitions to the massacre in Paris. Then, back to Babylon, where Griffith swiftly returns to the battlefield, followed immediately by The Dear One’s train-chase scene as she attempts to save her beloved. The Women Who Rocks the Cradle. Seamlessly shifts back to Paris, then to the scene of Brown Eyes being executed from the train. Three different stories unfold in a frenzy: the dead, the dying, and those awaiting death.

Griffith, in line with the story, also includes various African American extras alongside Madame Sul-Te-Wan. What’s even more intriguing is that, for a few seconds, he may depict a same-sex love. As the city is on the brink of collapse, Prince Belshazzar, about to go into battle with his people, is stopped by Mighty of Valor, who grabs him and kisses his hand. Subsequently, Belshazzar and Valor gaze deeply into each other’s eyes and embrace, sharing a kiss. While one could argue that this kiss is an expression of the respect accumulated over years between two characters facing death, it’s also quite likely that those who wish to interpret the film from a queer perspective have a valid point.

“Intolerance” was also a film that stirred controversy. This time, accusations of Jewish racism arise in the scene of Jesus’s crucifixion. All Jews in the crucifixion scene are depicted in an unflattering manner. However, the studio intervenes, wanting a decrease in the representation of Jews and an increase in Romans. Similarly, the studio desires an increase in sexual scenes in the film, but Griffith is not receptive to this idea. However, ultimately succumbing to pressure, he is compelled to comply with the studio’s demands.

A New Era

“Intolerance” was a successful film, although not as successful as “The Birth of a Nation”. Despite achieving success at the box office, the film incurred losses due to Griffith’s insistence on having large orchestras. Failing to meet expectations, Griffith took a break from filmmaking for the first time since 1908, returning in 1918 to resume where he left off.

In 1915, World War I broke out. Initially, America remained distant from the conflict, but in April 1917, following an attack on a trade ship off the European coast, the decision was made to join the war. During this time, Griffith was summoned by the British government to contribute to war-related efforts. Describing it as the greatest pride of his life, Griffith traveled to active battlefields to shoot footage. “Hearts of the World”, released in 1918, was a fictional war story interspersed with real battlefield scenes. Despite directing war films throughout his life, inspired by stories from his father, Griffith was deeply affected by what he witnessed during filming, later expressing disillusionment with the concept of war itself.

In 1919, Griffith played a significant role in the establishment of United Artists, which continues its activities to this day. Unwilling to be under the control of major corporations and desiring to produce films freely, Griffith, along with Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks, founded United Artists. Although not as powerful as major studios, United Artists became one of the important firms of the studio era. The first film released under the studio was also Griffith’s.

“Broken Blossoms”, released in 1919 and starring Lillian Gish, was another film that caused trouble for Griffith. The film, depicting a young girl finding solace from her father’s constant abuse in the shop of a Chinese man, was vetoed in England for its depiction of “child abuse”. Perhaps showcasing Lillian Gish’s career-best performance, the film, shot during the silent era, contained some of the loudest cries ever captured on film. So much so that a passerby thought something sinister was happening inside and attempted to enter to stop the filming.

The film was Griffith’s classic Russian Ending product. Once again, everyone was dying at the end. When Adolph Zukor, the owner of Artcraft, said he wouldn’t release the film due to discomfort with this situation, Griffith bought the film from him for $250,000 and released it under United Artists. The film, which earned a serious income of $700,000 at the box office, is considered a must-watch for many today.

Griffith also faced criticism for racism in “Broken Blossoms”. Although he faced criticism for casting the character Cheng Huan played by American Richard Barthelmess, Griffith explained that he took this approach because he believed that the American public, especially due to Sinophobia, would not accept a Chinese actor in the lead role.

Another career film by Griffith was released in 1920. “Way Down East,” depicting the drama of a single mother and her child, became the most successful film at the box office in 1920. The film, especially remembered for its river scene, showcased another career-best performance by Lillian Gish. Lillian Gish lying on a real ice floe, and Richard Barthelmess saving her at the last minute, is one of the most terrifying scenes witnessed in cinema history.

Returning to the streets of France in 1921, Griffith directed “Orphans of the Storm,” in which the Gish sisters shared the lead role. The film depicted the drama of a blind girl and her sister seeking a cure for her. It had a political message, attempting to address the increasing threat of Bolshevism to the government in America. Interestingly, Griffith had actually signed an ironic work, as important filmmakers in the country he criticized saw Griffith as a significant figure and a model influencing their cinemas.

Drifting Outside

After “Orphans of the Storm,” Griffith’s career began to decline. Although he managed to make a film every year until 1931, interest in his cinema diminished. Hollywood was changing. New directors were emerging, and slapstick comedy had become the new fashion of the era. His partner, Chaplin, along with rivals Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, had the most popular films. Griffith couldn’t keep up with the changing world. The tragic endings he never wanted to give up significantly reduced interest in his films. In 1924, when his directorial work “Isn’t Life Wonderful” failed at the box office, he had to leave United Artists.

In 1927, with the advent of sound in cinema, the film industry underwent a profound transformation. What the moguls saw as a passing fad, sound, garnered interest from audiences. Studios adapted to the new system by establishing studios to accommodate the new trend. With the arrival of sound, not only did the film production processes change, but also the film styles. Slapstick comedies, which were the number one at the box office at that time, suddenly decreased, making way for films filled entirely with dialogue.

Griffith, with his 1930 film “Lincoln,” tried to keep up with the sound film craze, but the film was considered boring. Struggling to find work and even adapt to the cinema culture of the time, Griffith turned to alcohol during this period. In 1931, he directed his ironically named final film, “The Struggle,” in which he tried to portray how families fell apart due to alcohol. However, old habits die hard. Ending the film again with a tragic final, Griffith faced a veto from the studio and had to change the finale with a happy ending. By portraying a man who loses his family due to alcohol in the film, Griffith may have been expressing himself. After “The Struggle,” Griffith retired from cinema, becoming one of the victims of the studio system and falling into oblivion for a long time.

About Him

When Griffith passed away on July 23, 1948, he was still a respected figure. The Directors Guild of America (DGA) began awarding the D.W. Griffith Award in 1953. In fact, in 1975, a special stamp was even issued in his honor. However, despite his death, his racism did not get off his back, and under pressure, the DGA changed the D.W. Griffith Award to the Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

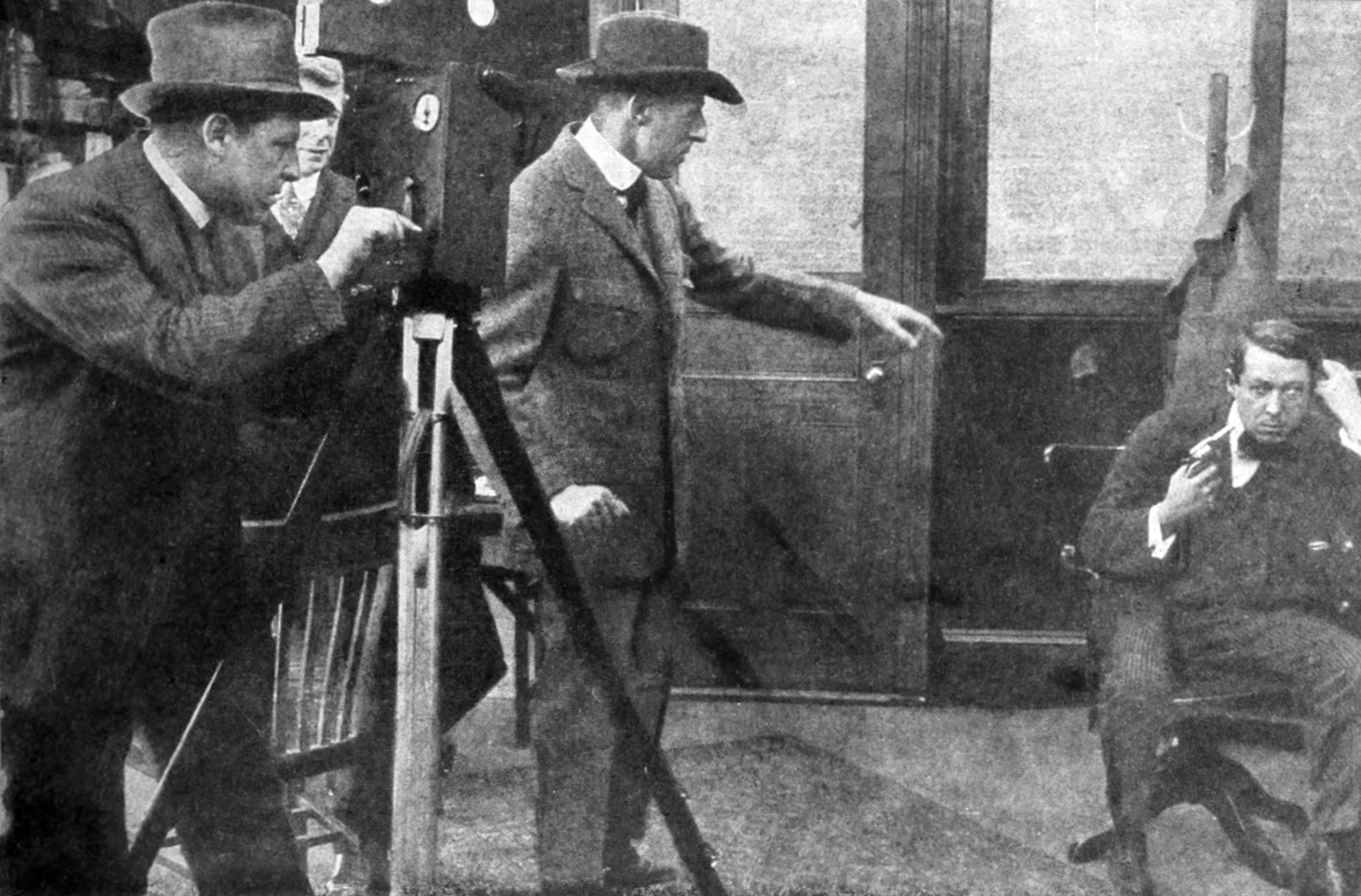

Griffith was a hyperactive director. He didn’t just settle for sitting behind the camera; he would also step in front of it to show his actors how to perform. Even from behind the camera, he would constantly give directives to his actors, never letting go of his straw hat and the megaphone he used to address them. To many, Griffith was the first director stereotype in Hollywood.

At the same time, Griffith was a character full of contradictions. Throughout his life, having heard stories of the Civil War from his father, Griffith depicted the Civil War in his films numerous times. Sometimes he told the story from the perspective of the North, and other times from the perspective of the South. Interestingly, he always tried to show in his films that war was constantly a bad thing. In “In the Border States,” he portrayed the humanity of Confederate soldiers through Union soldiers, while in his infamous film “The Birth of a Nation,” he depicted a Confederate soldier giving water to a Union soldier. In the same film, by showing soldiers dying in each other’s arms, he tried to emphasize the brotherhood between the North and the South. Similarly, portraying Lincoln’s constructive side was for the same reason.

However, the same Griffith also tried to portray African Americans in a completely unrealistic manner in his films, effectively writing the book on racism. It’s difficult to understand why he would attempt such an attack on a minority that couldn’t find representation on the silver screen, at a time when cinemas were segregated, and despite the abolition of slavery, they were deprived of even the most basic human rights. Especially considering Griffith’s view of the camera as an instrument that portrayed real life without lying, creating a film filled with fantastical black stereotypes are hard to comprehend.

Griffith claimed he adapted to the times, and his supporters consistently denied his racist side, but Griffith’s own statements often put him in difficult positions.

While many filmmakers of the time dared to cast black characters in their films and even went so far as to include close-ups of them, Griffith’s decision to portray his characters in blackface while also providing employment to a black individual like Madame Sul-Te-Wan raises serious contradictions. Why would a racist support someone to whom they were being racist? Why would someone who uses the camera for reality and tells stories from certain periods of history directly narrate a story that is evidently not true? Was avenging his father’s farm really that important?

Yet if we are still discussing Griffith today, it’s because of his contributions to cinema. Griffith was a visionary. He was the owner of many innovations, experimental works. He was the one who gave the cinema its first pre-film warning with “Those Awful Hats” in 1909. One of the cornerstones of today’s familiar “Please silence your phones” warning before films owes itself to Griffith.

The action scenes he shot during the Biograph era, the close-ups that reflected fear and love most deeply, the colossal choreographed dances he staged set him apart from other directors. Griffith was even among the first directors to experiment with sound in cinema. Before “Dream Streets” premiered in 1921, Griffith appeared on the screen and spoke to the audience.

These days, it’s unfortunately quite difficult to separate art from the artist. Even though it’s in vogue to try to cover up the mistakes of the past by toppling statues, there’s an important thing that’s being forgotten. If we are living in a world where all the problems are gradually diminishing today, it’s because of the mistakes made in the past.

But D.W. Griffith was not just a mistake. He was the one who laid the foundations for the modern narrative style of cinema. While “The Birth of a Nation” deserves all the criticisms for its content, it also deserves all the praises for its manner of conveying that content. It’s unfortunate that the subject of the first complete film in history is wrapped around racism.

But Griffith wasn’t just “The Birth of a Nation” also. With over 400 films to his credit, Griffith brought new languages, actors, and styles to cinema. While many of his contemporaries labeled him as the “Father of Film,” those who came after him fell in love with cinema by watching him.

Griffith is one of the main reasons why cinema is loved and accepted as a serious profession today.

Sources and Further Information

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey. “The Oxford History of World Cinema,” Oxford University Press (1999)

- Teksoy, Rekin. “Rekin Teksoy’un Sinema Tarihi,” Oğlak Yayınları (2014)

- Scognamillo, Giovanni. “Amerikan Sineması,” Alternatif Üniversite (1994)

- Robb, Brian J.. “Silent Cinema,” Oldcastle Books (2007)

- Cousins, Mark. “The Story of Film: An Odyssey” (2011)

- Brownlow, Kevin & Gill, David. “D.W. Griffith: Father of Film” (1993)

- Brownlow, Kevin & Gill, David. “Hollywood” (1980)

- Neely, Hugh Munro. “Star Power: The Creation Of United Artists” (1998)