Have you ever delved into the realm of Russian literature? Perhaps indulged in the works of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, or Gogol? Within Russian literary tradition, narratives often unfold amidst a backdrop of snow-laden, somber, and bleak atmospheres. Characters are imbued with shades of grey, their lives fraught with anguish, their existence a burden. Each individual contends with life’s adversities in the most morally ambiguous of struggles merely to survive. Such a disposition pervades the entirety of Russian literature.

Following the discovery of cinema in 1895, this somber existential mood transitioned from literature to the silver screen. Although the evolution of cinema in Russia did not progress as rapidly as in other nations, it harbored pioneers who laid the foundations and shaped its structure. Lev Kuleshov, through his experimental demonstration of perceptual differences between scenes, contributed significantly, while Sergei Eisenstein became renowned for his dramatic and metaphorical utilization of montage, showcasing it to the world.

However, figures like Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and their contemporaries, such as Vsevolod Pudovkin, belonged to a later generation of filmmakers. Their cinematic endeavors unfolded under an entirely new regime—one that sought to impose its own personal vision onto cinema. As the era of cinema’s propagandistic application began to burgeon, Russia emerged among those adept at harnessing this approach. Yet, despite the subject matter of my discourse ostensibly tethered to the regime itself, it pivots its focus to a time preceding their ascendance.

Admittedly, as I pen these lines, Russia occupies a somewhat contentious position on the global stage. While it may seem untimely to broach subjects concerning Russia, the essence of the matter I seek to elucidate actually harks back to the foundational periods that precipitated Russia’s aggressive stance. Indeed, exploring these origins may even serve as a poignant endeavor in understanding the present climate.

WHAT IS A RUSSIAN ENDING?

Recently, I asked a friend who had been immersed in Russian literature: “Do you recall any Russian novels with a happy ending?” Her response was negative. It wasn’t a surprising answer. Happy endings are not common in Russia’s realistic and metaphorical landscape. With the advent of cinema, the melancholy of literature found a new medium of expression. This melancholy became somewhat of a staple for a while. Films concluded not with flowers but with tragic endings, despondent characters journeying into the distance, and villains triumphing over the virtuous. As we are accustomed to these days, the conclusion did not favor the triumph of the righteous. The finales perfectly embodied the notion of a bitter end. This approach came to be known as the “Russian Ending.”

The nascent period of cinema was replete with films culminating in sorrowful sentiments. Characters found themselves trapped in dire straits, unable to escape, and the film would often end there, or they would squander their lives as slaves to the devil, having bartered away their souls. This phenomenon persisted even within the realm of horror cinema, my most extensively examined area of interest. Films like “The Queen of Spades” (1910-1916), Yevgeny Bauer’s “Posle Smerti” (1915), and Wladyslaw Starewicz’s “The Portrait” (also 1915) similarly failed to offer a resolution with a positive connotation. Regardless of the outcome, the answer to the question “Did it end well?” was always a resounding “no.”

However, the longevity of this epidemic of tragic endings proved short-lived. The sorrowful conclusions transplanted from literature to cinema would gradually yield to the realities of life. Russia found itself ensnared in a cycle of suffering so profound that it surpassed the imagination even in films. Hence, there would soon be no need for such cinematic expressions. Moreover, the world itself was changing; interest in bitter conclusions was rapidly waning.

RUSSIAN EMIGRANTS

With the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Russia’s perspective on cinema underwent a complete transformation. The revolution cleaved the cinema industry into two factions: those seeking to perpetuate the accustomed order and revolutionaries intent on eradicating the pre-revolutionary cinematic norms entirely. Many individuals, astonished by the unfolding events and apprehensive about their own fates, felt compelled to depart the country in the aftermath of the revolution. Consequently, numerous Russian artists dispersed to various corners of the globe, carrying with them their tales of woe—the ethos of the “Russian Ending.”

The general destinations for Russian emigrants included Germany, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Hollywood. These individuals continued their artistic endeavors and perspectives in their adopted countries and eventually began forming their own communities. It is imperative to mention a few notable figures from this diaspora.

Joseph N. Ermolieff relocated to Paris and established what would later become known as Ermolieff Film, soon to be renamed Albatros. The company played host to directors such as Yakov Protazanov, Alexander Volkov, Vladimir Strizhevsky, and Victor Tourjansky. Actors Ivan Mosjoukine and Natalya Lissenko were also among the luminaries associated with this firm. Russian-Polish animator Ladislaw Starewicz was another figure who resided in France, continuing his projects in his own studio.

Similarly, Germany was populated with a plethora of Russian emigrants, so much so that emigrants from France and Germany occasionally exchanged places to work on projects in these countries. Ermolieff, Tourjansky, Volkov, and Mosjoukine were prominent figures among them. Notable actors in German films included Vladimir Gaidarov, Olga Gzovskaya, and Olga Chekhova.

Italy, likewise, was a hub for active Russian emigrants. Director Alexander Uralsky, actresses Tatiana and Varvara Yanova, and actors Ossip Runitsch and Michael Vavitch were significant figures in Italy.

Vera Orlova and Vladimir Massalitinov were notable figures who made significant contributions in Czechoslovakia. Similarly, Vera Baranovskaya, who settled in Prague, was among the prominent figures there.

By the mid-1920s, Hollywood had become a frequent destination for Russian emigrants. Tourjansky and Mosjoukine abandoned their European adventures and headed to Hollywood. Ukrainian-born Anna Sten, Maria Ouspenskaya, Vladimir Sokoloff, and Mikhail Chekhov succeeded in finding roles in Hollywood, while directors such as Ryszard Bolesławski, Fedor Ozep, and Dimitri Buchowetzki also found opportunities to make films.

THE CHANGING WORLD

While Russian emigrants harbored hopes of returning to their homeland once the revolution subsided, the world was evolving. Upon settling in new lands, these emigrants initially adapted their cinematic styles to the cinemas of their host countries. They continued to employ pre-revolutionary cinematic techniques and the concept of the Russian Ending. However, their dolorous cinematic narratives began to lose their appeal over time. Particularly after the 1920s, there was a complete transformation in the global understanding of cinema. The comedy genre, especially with the rise of Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd, began to captivate audiences worldwide. Advancing cinema techniques also facilitated the production of films in various genres.

French audiences labeled the films of Russian emigrants as “conservative.” Moreover, the Russian Ending, a device they never abandoned and almost invariably employed in their movies, ceased to captivate viewers. Audiences no longer found tragic endings compelling unless they adhered to the conventions of classical melodrama. Recognizing this shift, Russian emigrants gradually struggled to adapt to the emerging cinema trends from the West. However, they were reluctant to abandon their style. Consequently, they divided their films into the real world and the realm of dreams.

Although they continued to craft narratives reminiscent of the dolorous world of pre-revolutionary Russia and sought to convey their intended messages with the desired endings, they eventually began to awaken their characters to the realization that everything was merely a dream. Thus, while providing Russian audiences with the sought-after tragedy, they also created an atmosphere of a happy ending for European viewers. Preparations were made for a Russian Ending, leading to a tragic finale, but ultimately, the characters would awaken from their nightmare, realizing that everything had been a mere illusion.

In contrast to Europe, Hollywood was far less accommodating to Russian emigrants. Unyielding in their standards, Americans did not allow emigrants to adapt their own styles. Hollywood, especially following the aftermath of World War I, emerged as the sole authoritative figure in cinema, directing the global understanding of film single-handedly. Wresting control of cinema from France, Americans began to export their own cinematic style worldwide.

Especially in the 1920s, American theaters resounded with laughter. Audiences typically frequented cinemas for amusement and entertainment. Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd were pioneers of this comedic wave. The period between 1920 and 1928, particularly in Hollywood, held an outlook entirely contrary to that of Russian emigrants. Consequently, emigrants found themselves compelled to relinquish their style and adapt to the prevailing trends.

The advent of sound in cinema with the release of “The Jazz Singer” in 1927 revolutionized everything. Studios underwent extensive renovations to accommodate sound recording, necessitating the transition from outdoor to indoor shooting. Thus, by 1928, the Studio System, which would span 40 years, came into being. With the Studio System, the comedy of the 1920s gave way to melodramas and films featuring dialogue. This new era could have been advantageous for Russian emigrants, as the transition to melodramas might have heralded the return of the Russian Ending to cinema. However, quite the opposite occurred, as the Russian Ending was forced into obsolescence.

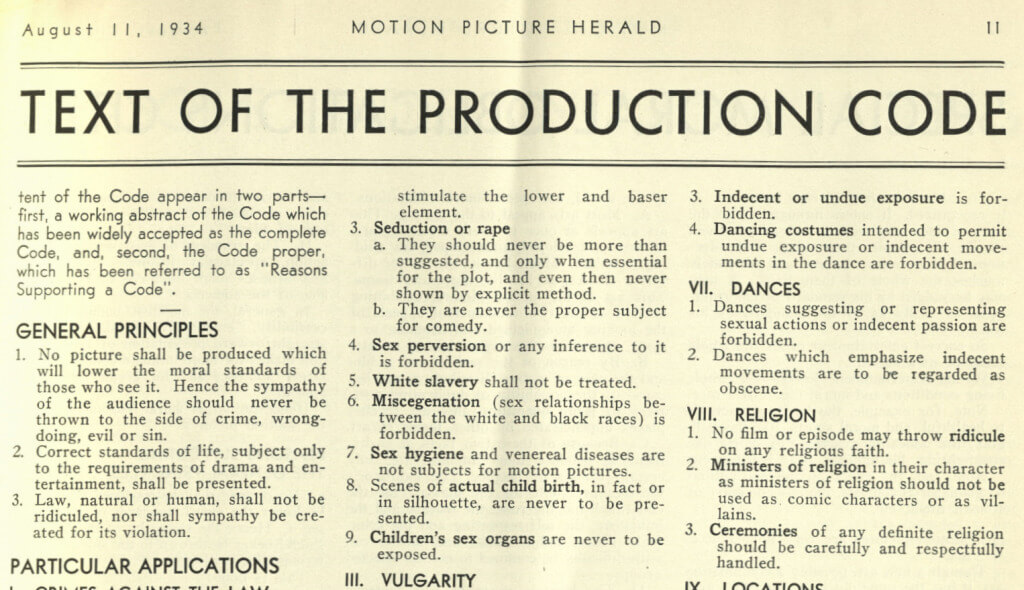

The “Roaring 20s,” marked by extravagant parties, celebrity culture, and scandals, exacerbated America’s conservative outlook, partly influenced by the film industry. A group led by Will H. Hays believed that immorality was on the rise and felt the need to regulate the film industry accordingly. This sentiment culminated in what would become known as the Hays Code, a set of laws aimed at enforcing moral standards in cinema. The most significant mandate of the Hays Code was the requirement for films to have a happy ending. Hollywood was thus compelled to produce films where the villain was punished, and the virtuous prevailed. Additionally, the code discouraged approaches deemed immoral and advocated for the avoidance of brutality and similar distressing elements.

The Hays Code merely exacerbated the ongoing transformation. Amidst World War I and economic turmoil, global audiences had already turned away from “tragic” narratives in favor of films that would entertain them.

THE FATE OF THE RUSSIAN ENDING

In truth, understanding both sides is not difficult. Russian emigrants sought to translate the dolorous tales of their upbringing onto the screen, while Europeans, satiated with wars and hardships, aimed to utilize cinema for amusement. Although emigrants departing Russia in the aftermath of the revolution initially managed to bring their sensibilities with them and succeed in creating art within this framework for a time, they eventually found themselves compelled to adapt to the rapidly changing world and the stylistic dominance of Hollywood. So much so that even Sergei Eisenstein, one of the most prominent figures in Russian cinema, designed his classic, “Battleship Potemkin,” drawing inspiration from D.W. Griffith’s film “The Birth of a Nation.”

While many emigrants returned to their homeland after the revolution, especially with the establishment of the USSR in 1922, numerous individuals continued their lives in the countries they had migrated to. Despite managing to prolong its existence for a time, the Russian Ending they carried with them eventually succumbed to the changing world, fading into oblivion alongside many understandings, names, and cultures, becoming a mere fragment of history.

Sources and Further Information

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey. “The Oxford History of World Cinema,” Oxford University Press (1999)

- Teksoy, Rekin. “Rekin Teksoy’un Sinema Tarihi,” Oğlak Yayınları (2014)

- Oylum, Rıza. “Rus Sineması,” Seyyah Kitap (2016)