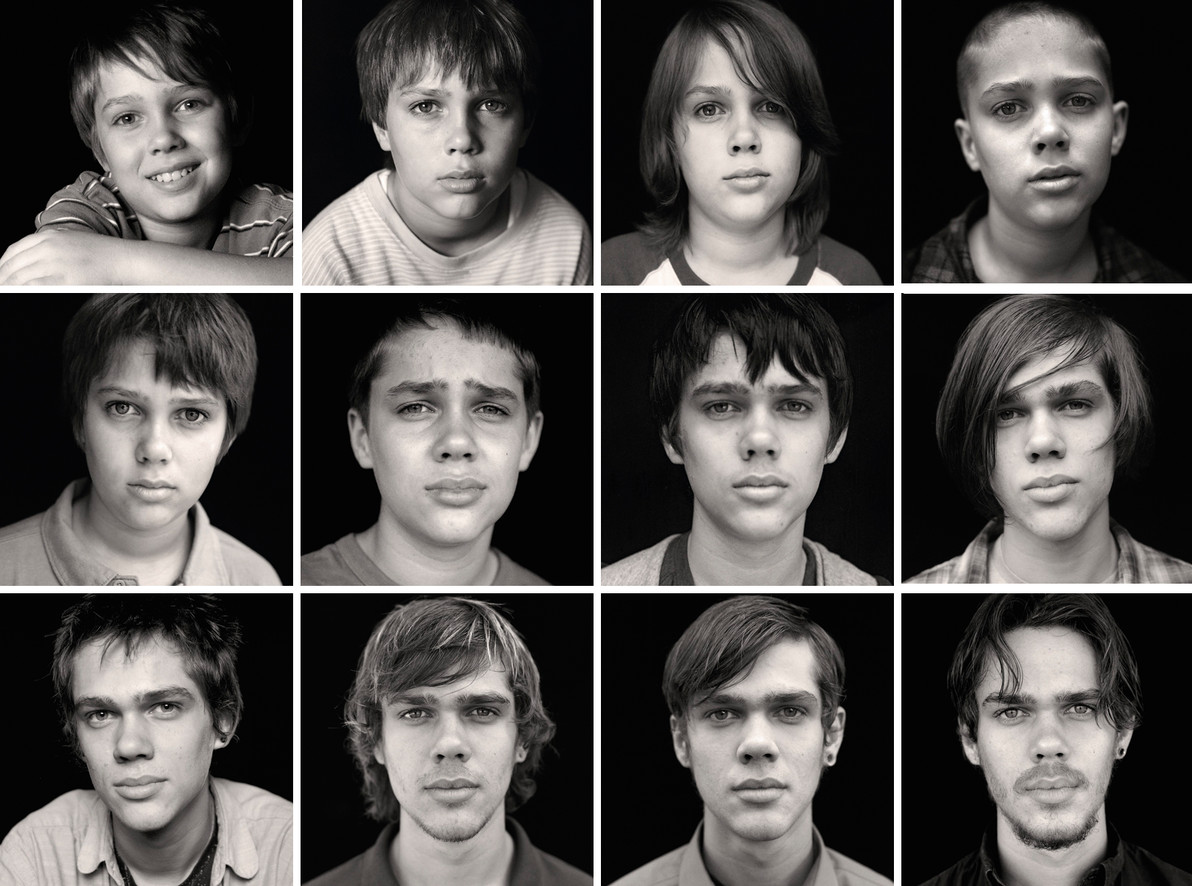

As we approach the end of the year, we can unequivocally declare “Boyhood,” wildly acclaimed by film critics, as the standout film of 2014. “Boyhood” has managed to impress everyone who has seen it, both in terms of its content and its remarkable 12-year production journey, as well as the audacity of conceptualizing such a project. To underline for those who may not be aware: The film was shot over the span of precisely 12 years. When the movie began, Ellar Coltrane, who portrayed the character Mason, was merely 7 years old. By the time the film concluded, he had blossomed into a 19-year-old young man attending university. This is what makes the film truly fascinating. It’s a film that was shot over 12 years without any fictional or makeup artifice.

However, “Boyhood” is a polarizing film, with as many detractors as admirers. The reason for some viewers’ disappointment dovetails with a point I want to address. Those who didn’t enjoy the film often cite the absence of a traditional script, a plot, or a conventional narrative structure. To some extent, they are correct. “Boyhood” doesn’t conform to a typical narrative structure with a clear beginning or end. It is an exploration of life’s continuum, with its start marked by birth and its conclusion by death. Thus, everything depicted in the film is a reflection of life’s ongoing development. The film offers a glimpse into a 12-year span between birth and death, with the chosen years being arguably the most transformative in a person’s life, both physically and spiritually. Essentially, we are witnessing what Mason would see if he were to die at the age of 19 as his life unfolds like a reel of film before our eyes.

Despite the absence of a traditional plot, the film is rich in details worth discussing. Mason is a part of many lives that come and go over the course of 12 years. At the film’s outset, Mason’s mother decides to separate from his father. Mason and his sister, who is also the director’s daughter, Samantha, begin living apart, and their father continually plays the role of the entertaining weekend visitor throughout the entire 12 years. Mason’s mother must endure many hardships to care for her two children. To overcome these challenges, she marries a college professor but eventually discovers that he becomes a heavy drinker many years later. In order to protect her children, she leaves him as well. Throughout this 12-year period, the children frequently change schools, but their mother constantly reinvents herself, even achieving the remarkable feat of becoming a university professor. The only constant is the father, who visits on weekends.

The children are the ones who need to grow in the film; the mother remains a stable, mature character, undergoing no physical changes, and we know she won’t. Yet, we witness that there is no age limit to learning and personal development during this journey. A few years later, the mother marries again and begins a brand new life for the children. However, this marriage also proves short-lived. The children are always in a state of flux, while the mother tries to anchor them to stability. Yet, we see that everything can fall into place with determination and time. Over time, the mother manages to get her life in order. Mason gets into college. Their father meets someone new, gets married, and even has a child. In the end, we see that with perseverance, everything can find its place.

What makes the film genuinely compelling is not only the struggle of the children and their mother against life’s challenges but also how miraculous the process of growing up is. “Boyhood” vividly demonstrates the profound truth behind the statement, “You were so adorable as a child.” At 7 years old, Mason is undeniably sweet, charming, and innocent. They say a leopard can’t change its spots, but the carefree child at age 7 remains the same at 19. However, what’s remarkable is how we witness, in the span of three hours, the gradual transformation from that sweet, innocent boy to someone who has become coarser, matured, and, in a way, distanced from his childhood. It’s nearly impossible for people with siblings of different ages or parents with children not to be moved while watching this film. The saying, “They grew up in my hands,” couldn’t be more accurate. At the beginning of the film, we see an endearing child, but by the end, he has changed dramatically, still reminiscent of his childhood but also a world apart. The child who once sat down to eat a meal placed before him is now in the middle of the film, kissing his girlfriend in the back of a car. Or the child who used to drink milk now indulges in smoking and alcohol.

I am certain that those who appreciate the film do so with this perspective in mind. Not only is it a highly experimental work in terms of its production, but it also tells a 12-year-long story in a ‘realistic’ manner, which is undeniably impressive. Personally, as someone who has grown up alongside people younger than myself, I found myself emotionally connected to the film. I have witnessed people who were just starting school, and now I sit down and discuss work with them, or we go out for drinks together. Recognizing the tremendous nature of this change, I thoroughly enjoyed the film. Imagine having a sibling; you’re there with them on their first day of school. Then time passes, and they announce they’ve been accepted to university. They are no longer weak, frail, or dependent on others.

At the beginning of the film, Mason is under the protective wing of his mother. As time goes on, even his mother doesn’t know what he’s up to or where he is. The critics have rightfully placed “Boyhood” in the top three of their lists because the portrayal of change is presented with absolute authenticity. In my opinion, this film should be on the must-watch list. Director Richard Linklater deserves a special mention. As someone well-versed in the history of experimental cinema, I can confidently say that a production like this is unheard of, at least in my knowledge. Even for achieving such a feat, Richard Linklater will forever remain unforgettable to me.

Of course, condensing 12 years into 3 hours is no easy feat. The director skillfully manages this in the editing, seamlessly advancing the years through abrupt cuts rather than fade transitions. They present us with a clean and fluid depiction of 12 years within those 3 hours. As the years progress, I believe the film touches upon relevant themes: the first encounter with women and the female body, the breakdown of the family, children being pulled along by family members, changing schools, constantly evolving social circles, the father’s visits and conversations, sexual encounters, difficulties with stepfathers, and much more. In particular, the conversations between the father and the children are well-chosen. They consistently revolve around life and discussions aimed at enlightening the children. This is because when your child reaches 14 or 15, they will start showing an interest in the opposite sex, and you will need to have these conversations. Since this is a situation that can happen to any family, the director has chosen to include such discussions throughout the film.

In essence, “Boyhood” can be described as one of the most fascinating, arduous, and perhaps the longest-filmed works in the history of cinema. Personally, I view it as a masterpiece that should be watched. It will hold special significance for families with children, older siblings with younger ones, or those who have grown up alongside others. We witness children growing up before our very eyes within 3 hours. Without realizing it, 12 years flow before our eyes. There is no clear beginning or end to the film; instead, it offers us a 12-year slice of life, focusing on the years when a person undergoes the most significant physical and mental changes. If you’ve read this far, I urge you to find the film and start watching it immediately. I’m confident it will pique your interest; “Boyhood” is truly a rare gem that deserves a place in your collection.