On the 28th of December 2023, the cinematic art celebrated its 128th anniversary. When the Lumière brothers stumbled upon the discovery of cinema 128 years ago, they could not have fathomed its widespread appeal and reach to the masses. In their eyes, cinema was a fleeting fancy, a mere discovery. However, today, cinema stands as a narrative that speaks in billion-dollar languages, filling theaters with millions of spectators and emerging as the seventh art. What they uncovered was undeniably extraordinary; it resembled our dreams. It was an alternative mode of storytelling, a powerful mass weapon, a brand-new plaything, an experimental platform. Over the course of 128 years, people explored every conceivable genre of this art form, producing monumental works. Some attempted to depict love in all its facets, others preferred showcasing the external facade of our everyday lives, and some amused people with their dreams. On the stage, significant works from distinguished figures were observed—those applauded standing, those watched with tears, those unwatchable due to laughter, and those unforgettable once witnessed.

128 years ago, when the Lumière brothers first showcased their creation, the audience was shocked. In a 10-second video where a train entered a station, people believed the train was approaching them, marveling at the spectacle. Someone was there that night. Enchanted by what he saw, captivated and fell in love. And that love, which began that night, would alter the course of cinematic history. Perhaps even the colossal presence of cinema today owed itself to that individual.

The year was 1895… Thomas Edison embarked on a world tour with his newly coined invention, the Kinetoscope. The device he developed was a single-eyed film box that rapidly streamed photographs, creating the illusion of motion. Citizens paying 60 cents could place their eyes against the Kinetoscope and watch intriguing films shot by Edison and his team. One of the stops for the Kinetoscope was in Paris, France. Edison secured a shop on the street of Théâtre Robert-Houdin.

Among those who witnessed this one-person spectacle was Antoine Lumière. A photographer by profession, Antoine Lumière was so impressed by what he saw that, upon leaving the store, he immediately went to his sons, Auguste and Louis Lumière, urging them to invent something similar. Thus, the creative process of the Lumière brothers’ discoveries, which would span 128 years, was set into motion.

Now, let us shift our narrative focus to the central character of our story: Georges Méliès.

Who is Georges Méliès?

Georges Méliès was born in 1861 in Paris as the son of a wealthy shoe manufacturer. Growing up, he watched fairies on the stages of Theatre du Chatelet and Théâtre de la Gaîté. His interest in art began in childhood, and though he aspired to study Fine Art, unfortunately, he was vetoed by his father, compelling him to follow the family trade. Consequently, he started working in the shoe factory, where he learned everything about machines and operations.

He later married Eugenie Genin, the daughter of another affluent shoemaker. He continued in the shoe business. After a while, his father sent him to London to learn the industry. But his mind was elsewhere. His dreams still revolved around fine art. London, at the time, was the capital of illusion shows. He spent his days, especially at the Egyptian Hall, immersed in the intricacies of illusion. Upon his return to Paris from London, shoes were no longer on his mind.

Everyone expected him to continue in his father’s trade, but upon his return, he was determined to revisit his childhood. The magic tricks he performed as a child and puppet shows that entertained people were still vivid in his mind. As the saying goes, “a tree bends while it is still young”; Méliès’ curiosity for art did not remain a mere hobby.

Méliès shared the city with Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, one of the greatest illusionists of all time. Théâtre Robert-Houdin was one of the city’s most famous spots. However, when Mr. Houdin passed away in the summer of 1871, the theater faced difficulties. His wife, François Marguerite Olympe Braconnier, attended to the condition of the theater. While the theater continued its performances, it underwent several changes in management. In the summer of 1888, Méliès became the new manager of the theater.

In 1888, Father Méliès retired and divided the shares among his children. Méliès, selling his shares to his siblings, acquired the theater with the money at hand, embarking on the pursuit of his dream job—performing magic. He was good at it. He began stage shows at the Parisian Salon, Cabinet Fantastique, Grevin Museum, and the Theater of Magic inside Galerie Vivienne. With his magic shows, he gained recognition and fame, so much so that the Lumière brothers decided to invite him to their first Cinematograph screening, following after an encounter on the stairs of Théâtre Robert-Houdin after one of his performances. One of the Lumière brothers reportedly said to him:

“Mr. Melies, since you are in the habit, during your shows, of suprising the audience, I would love to invite you to come to the Grand Cafe. “Why” I answered. Because you will see something that might surprise you.”

– Georges Méliès

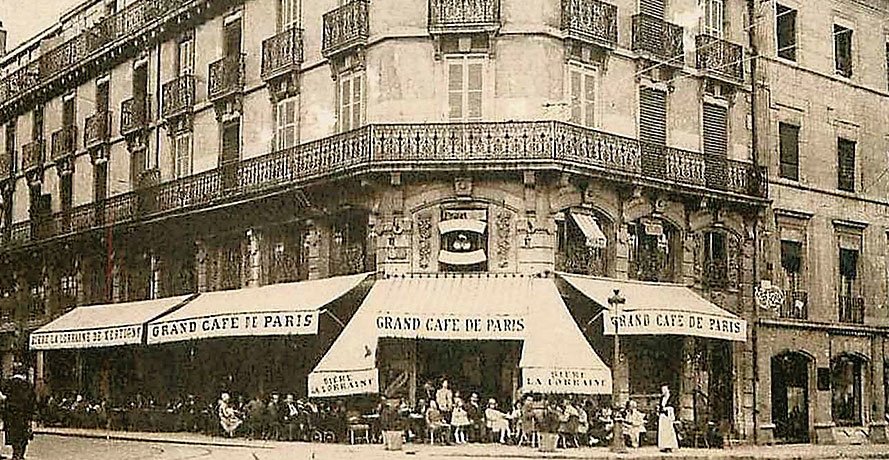

Grand Cafe

Georges Méliès was among the invited guests at the first screening held on December 25, 1895. Like everyone else, he took his seat. However, he was smarty pants that day. He wasn’t particularly impressed by what he saw until the still photographs started to come to life and move.

“When I first saw his camera, projecting still photographs, at the beginning, I said “you bothered me for projections, I’ve been doing them for 20 years. Nothing extraordinary about them.” Then Suddenly, I saw the character moving, coming toward us. A few minutes later, a train launched, it almost went through the screen, straight into the audience, we were all, I must say, absolutely astounded. I immediately thought, that’s my business, an extraordinary thing.”

Méliès’ journey in theatrical magic extended only until the first film screening he witnessed at Grand Cafe. Now, a new enthusiasm brewed within him: Cinema. He needed to own a cinema machine. After the screening, he promptly approached the Lumière brothers and inquired about purchasing the machine from them. However, the Lumière brothers, believing that cinema would not catch on, refused to sell him the machine. He was disheartened. Did he give up? Of course not. He charted the course of cinema history on his own. He laid the foundations of contemporary cinema, earning him the title of the “godfather of cinema,” as bestowed upon him by director Stan VanDerBeek.

First Films

When the Lumière brothers refused to sell him the cinema machine, Méliès persisted and built the machine from scratch. Once completed, his first destination was the streets. He ventured out, capturing the crowds, recording natural scenes from daily life, akin to the Lumière brothers. Then, something interesting happened; the machine experienced a glitch. Suddenly, it started working again. The resulting images surprised him. The people walking on the street had disappeared, replaced by others. This glitch marked the turning point that steered Georges Méliès in the history of cinema.

“It was simply a camera freeze that occurred while I was filming the cars on Opera square. Suddenly the Camera stopped. By the time we fixed it, the cars’ placements had changed, and I was surprised during editing, to suddenly see, instead of a madeleine-bastille omnibus, a hearse, and the whole family that followed.”

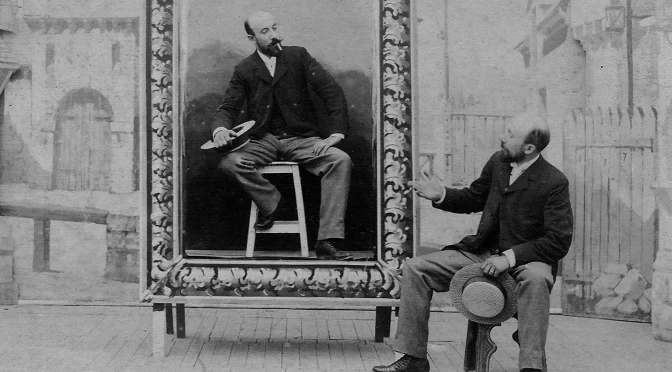

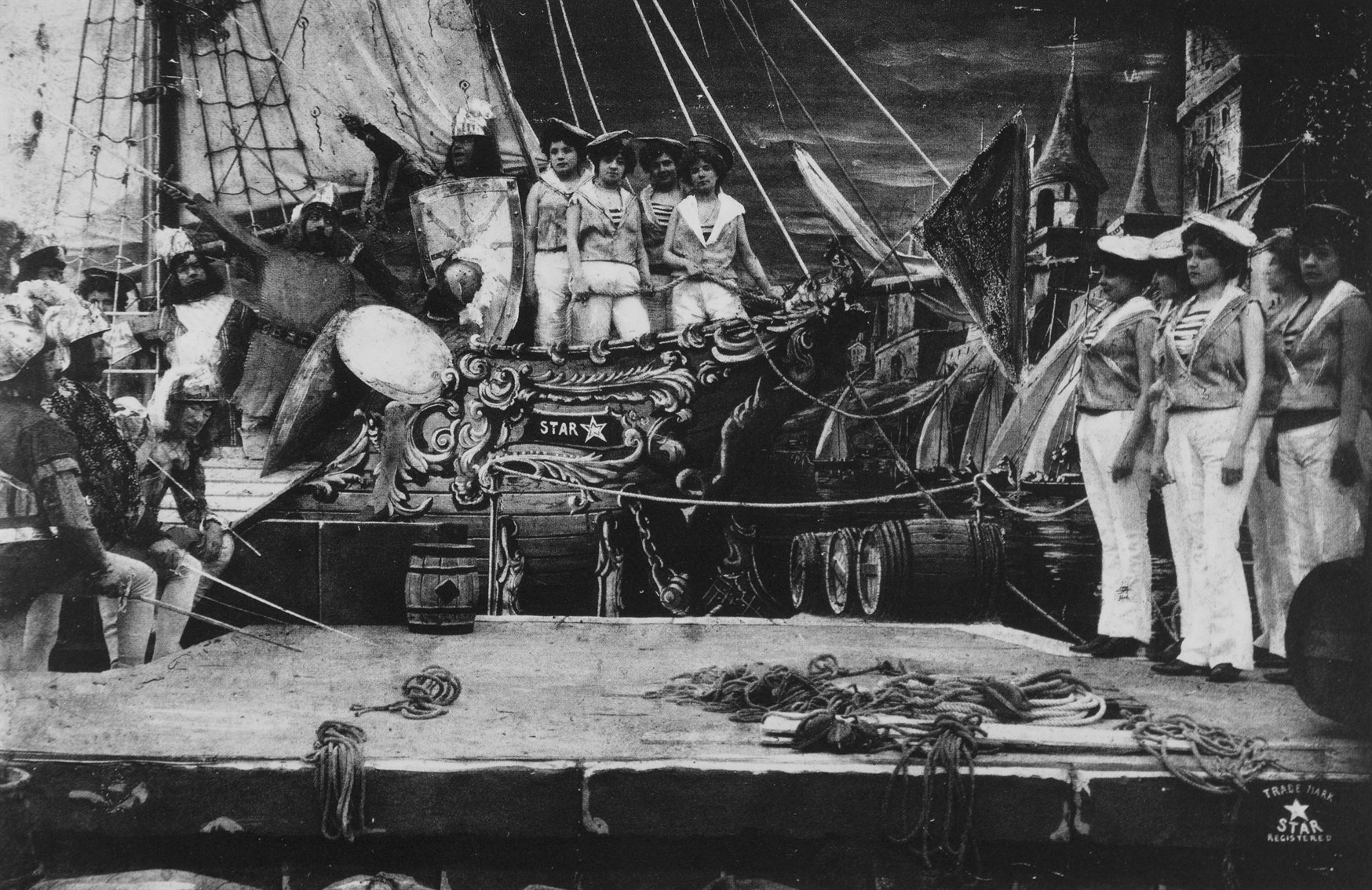

He adeptly utilized this newly discovered stop-and-start technique, using it to enhance his imaginative works. Initially, he filmed his own illusion shows, finding it easier with the new technique. In fact, this innovation made his illusions even more astonishing. The first video he shot was a short film titled “A Card Party.” Lucien Reulos, standing on his left in the video, was his only partner for a year. Together, they founded the brand Star Film, which would later host hundreds of films.

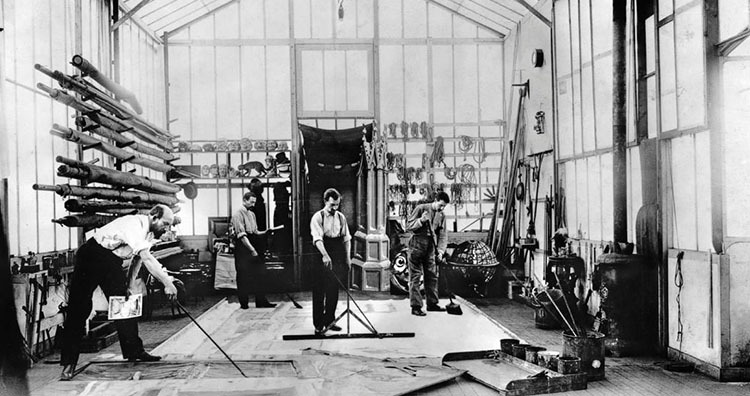

By the end of 1896, he had filmed approximately 78 movies, adding 53 more in 1897. From April 1896 onward, films were shown daily at Théâtre Robert-Houdin. However, this was not enough for Méliès. He decided to explore a different style. In 1896, he started filming films in his garden, in front of a backdrop. However, constant wind interference led him to establish Europe’s first film studio in Montreuil. Here, he filmed Cinderella, Joan of Arc, various monsters, demons, and perhaps the most important film in silent cinema history, A Trip to the Moon.

“My first studio was a big and long room of 33 ft by 20 ft, made entirely of glass. It was not set up at all, at the time, nothing like what I did later on. Later I built stage machinery, above and below it, in order to create great fairytales just as I created great shows.”

Méliès was different from other filmmakers. His mind was lurid. He was extremely imaginative, drawn to devils, creatures, and wars. He adored the unreal stories. He was the director of stories that never happened, influenced by the fairy tales he saw in Chatelet or Gaite Theatres during his childhood, unable to forget them.

The Mastery Period

We can understand his exceptionally different mind through his famous film, A Trip to the Moon. During an era when something deemed ‘impossible’ by human standards found a place in his mind. What if people went to the moon? It had only been seven years since the discovery of cinema. Yet, he already wanted to go to the moon. And he did. He always had a fascination with the moon. In films shot before 1902, the moon descended to the Earth, taunting his characters. However, in 1902, Méliès’ characters decided to go to the moon and taunt it. The film’s shoot, consisting of 30 scenes, took three months. But the effort was worth it, as Méliès is primarily remembered today, especially for A Trip to the Moon.

Charles Pathé, an influential figure of the time, produced a similar film titled Excursion Dans la Lune after Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon. In fact, Charles Pathé copied Méliès in many of his films. And he wasn’t alone. Many directors of that era were directly copying Méliès’ films. Even directors from his own country, such as Segundo de Chomon and Ferdinand Zecca and the American Edwin S. Porter, who was thousands of kilometers away, were making films resembling his works. Ironically, in 1911, a year when Méliès was not making films, Pathé expressed interest in financing his filmmaking endeavors.

He was the one who could detach his head and place it on the table, inflating it like a balloon, as well as compose songs by drawing musical notes with his head. He created demons that troubled the chef in the kitchen and made paintings come to life to entertain. He initiated the horror genre, owned the first science-fiction film, and was even the owner of the first colored film. With unwavering dedication, he personally colored all the negatives one by one to showcase colored presentations.

“In George’s hands, the camera didn’t attempt to record reality but presented a world where fantasy and magic reigned supreme. “

– Lumiere Brothers

From the year he took the camera in his hands in 1896 until 1913, Méliès directed a total of 520 films. He wasn’t merely behind the camera; he was involved in almost every aspect of film production. In most of his films, he played the lead role. He had a hand in the design of sets and drawings, exploring depth in scenes with the backgrounds he designed. He was a hyperactive character. Instead of writing scripts while filming, he preferred to keep the story in his mind. Most likely, the period between 1896 and 1913 was the most beautiful time of his life. He was shooting films in the morning in his studio, then performing magic in the evening in his theatre. Of course, he derived immense pleasure from these activities because he did not view them as work.

Studio Days

Throughout Méliès’ filmmaking career, he ventured into many different stories and genres. While he predominantly left his mark on fantastical works, he occasionally delved into significant subjects. One such instance was his direction of “The Dreyfus Affair” in 1898.

“French Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a graduate of the École Polytechnique and a Jew of Alsatian origin, was accused of handing secret documents to the Imperial German military. After a closed trial, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment.”

– Wikipedia

At that time, people relied on newspapers for information as there was no concept of video news. Taking advantage of this absence, Méliès transformed the scandal into a film, creating the first political film in history. In the movie, he even portrayed Dreyfus’s lawyer, Labori.

Despite venturing into various genres, from advertising to medieval films, during the active years of Star Film, Méliès’ preference was evident—the extravaganzas, also known as Trick Films. People filled small theaters to laugh and be amazed.

Méliès’ business was flourishing at first. To the extent that at one point in 1907, he established a second studio, enabling him to shoot two films simultaneously.

In February 1909, he assumed the presidency of the Film Publishers Congress held in Paris. This congress attracted pioneers of the time, such as Leon Goumont, George Eastman, Cecil Hepworth, and Pathe.

Méliès in America

As Méliès’ endeavors expanded, his brother Gaston became part of his business world. Opening up to the world with films was a constant idea in Méliès’ mind, especially concerning America. In 1903, the cinematic hub of the time, New York, witnessed the opening of an office at 204 East 38th Street. Gaston took charge of this office, initiating the sale of Star Film’s films.

Initially, business in America was promising. Gaston was at the forefront of protecting the rights and preventing unauthorized copying. Méliès had set up a dual-lens camera system in his studio, with one lens capturing a full-quality negative while the other produced a lower-quality negative. The second negatives were sent to New York, to Gaston.

In 1891, Thomas Edison obtained the patent for 35mm film, allowing him to claim royalties from anyone using it. In 1908, he established the Motion Pictures Patent Corporation (MPPC). Gaston wanted to join the MPPC so that Méliès’ films could easily be brought to America and distributed. However, Edison, aware of Méliès’ popularity, rejected the request, citing that their films could not be distributed in America due to US Patent violations.

In response, Gaston began producing his own films. In the firm named Melies Manufacturing Company, he made Westerns, dramas, and comedies. Gaston was aware that his brother Méliès’s style was losing its appeal, at least in America, where the audience was more interested in these genres. While Méliès was content with making money, he couldn’t say the same for his love of the films. He particularly felt that the establishment of a company in his name, producing different films, tarnished his reputation.

After the 1910s, the cinema industry shifted from New York to California. In 1911, Gaston moved the company to California, but during this relocation, his team left him for other companies. Gaston’s time in California did not go well, especially as new directors were making entirely new styles of films. This further diminished interest in Méliès’ films.

By 1913, Georges and Gaston had differences leading to a heated argument. Whatever transpired between them, the two brothers never saw each other again. Before leaving America, Gaston sold 50% of the company to the Vitagraph company in Brooklyn to ensure the film distribution could continue. During this time, Gaston stored his negatives in his friend’s basement since they were not financially valuable. Upon parting ways in America, Gaston traveled to various places such as Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia, Singapore, Cambodia, and Japan, producing a series of less successful films.

The World is Changing

At the beginning of the 1900s, the fate of the man who outlined the future of cinema history unfortunately did not unfold as joyously as his films. Despite continuing to produce films, he began to lose his grip on the rapidly evolving cinema market. During that period, cinema was transforming into a full-fledged industry. New directors and companies were emerging, and there was a significant increase in the number of movie theaters. With the rise of cinema theaters, the era of film rentals commenced.

During the industrialization, Méliès’ style, which favored extravaganzas or Trick Films, witnessed a declining interest. Fully aware of the situation, Méliès had his assistant, Manuel, create films suitable for the era, but the results were not as expected. America, gradually taking control of cinema held by France, began to influence Europe with its own style.

1913 might have been the worst year in Méliès’ life. Not only the American company but also Star-Film in France had to close due to these developments. Struggling due to the circumstances and needing to find a way to earn money, Méliès transformed his Montreuil Studio into a theater during World War I. Meanwhile, Robert-Houdin also served as a cinema, ironically, featuring Chaplin’s slapstick comedy films.

The world was changing, and the public’s expectations were distancing from old entertainments. Many new styles were developed, especially with the advent of cinema, and with the advancing cinema technology, more successful films were being made. Giovanni Pastrone, in 1914’s “Cabiria,” narrated legends on massive sets, while D.W. Griffith continued this trend, producing lengthy action films with “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915.

Méliès’ dreams, which had once placed him at the pinnacle of the world in the early 1900s, had become his greatest disadvantage as time passed. He couldn’t adapt to the changing world. Consequently, his economic situation worsened day by day. In 1922, he lost the Robert-Houdin theater. On top of that, the theater was demolished for the expansion of Haussmann Boulevard.

In 1923, due to debts, he was forced to sell the Montreuil studio. After staying vacant for a long time, unfortunately, it was demolished in 1945. Méliès, having lost everything, began to lose his rational thoughts. And one day, feeling that life was unfair to him, he made the decision to burn all his films in the garden of his house. He was so enraged that all his efforts, achievements, and dreams vanished in the flames. He tried to erase himself from history!

“I didn’t have anywhere to keep the hundreds of film negatives. In a moment of anger and exasperation, I ordered for them to be destroyed without realizing that I was doing something as imprudent as it was irreversible.”

Fortunately, copyright law came into effect only in 1911, and the concept of piracy was still plaguing artists in those years. Thanks to those who copied and illicitly screened his films, about 200 out of his 520 films managed to reach us today. Méliès was a clever man. Knowing that pirates could steal his films, he added his company Star-Film’s logos to them. But thieves were adept at thievery as well. They systematically found and erased these logos from the negatives.

Returning to Life

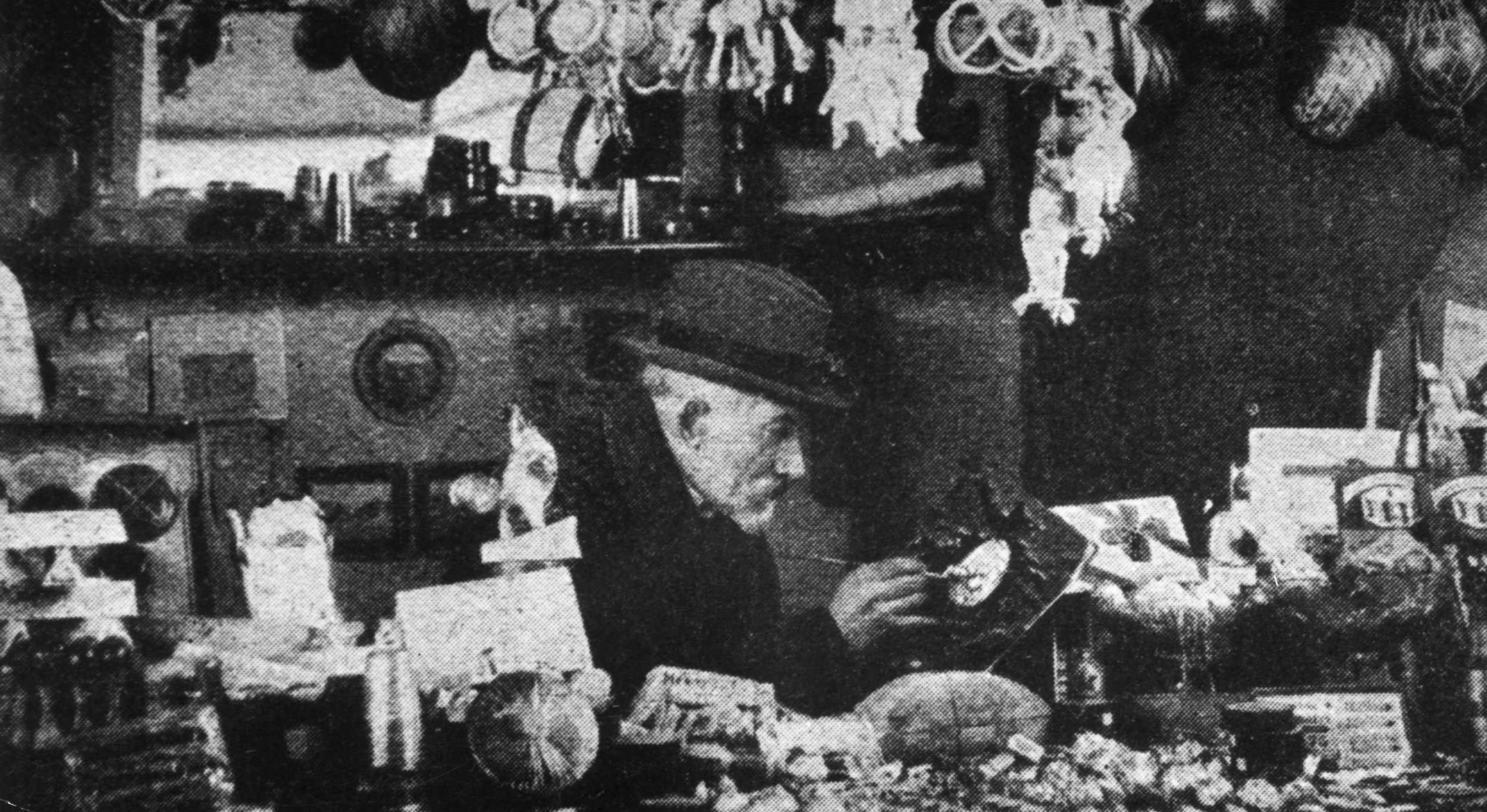

Méliès, unable to put his affairs in order, had raised the flag of bankruptcy. After burning his films, Méliès, who withdrew into seclusion, opened a small toy shop at the Paris train station and completely turned his back on cinema! Between 1925 and 1932, along with his wife Jehanne d’Alcy, he made a living by selling toys for 15 hours a day, 7 days a week, at the Montparnasse train station. In his free time, he painted famous scenes from his films. It was evident that he couldn’t forget them. But what he didn’t know was that others hadn’t forgotten him.

In 1929, two new cinephiles of the younger generation, Jean-Placide Mauclaire, and Paul Gibson, happened to see him at the Montparnasse train station and began to visit him regularly. These two cinephiles, familiar with Méliès’ films and his reputation from years ago, started working to restore Méliès’ fame. In December 1929, Mauclaire organized a special night for him at Salle Pleyel. During this gala, eight damaged films by Méliès were screened.

In 1931, France awarded him the Legion d’Honneur and provided him with a monthly allowance. Economically gaining a slight relief, Méliès settled in Chateau de’Orly with his wife in 1932. His granddaughter Madeleine, whom he had been looking after since 1930, joined him. During his time at Chateau de’Orly, Méliès was visited by many important figures. Henri Langlois, who would later establish the Cinémathèque Française; George Franju, who would make a documentary about him in 1952; the Italian painter Mimma Indelli; the father of animation Emile Cohl; the director of many early classics Carl Laemmle, and the famous Dada artist Hans Richter were among those who visited him.

During his time at Chateau de’Orly, Méliès had the chance to appear in front of the camera again. His last work was a cigarette advertisement. However, this cigarette commercial was like proof of why his films were no longer being watched. It was evident that Méliès, who was still making advertisements using the tricks of the early 1900s, was far behind the times.

Méliès passed away in 1938, spending his remaining years conversing with those who visited him and searching for his lost films. In his last years, knowing that he was respected again, I hope he found a peaceful farewell. Little did he know that after his death, filmmakers would inscribe his name in golden letters all around the world. Those who knew him, who knew what he had done, would somehow work for him to be remembered and for his name to reach the future. One of them was his granddaughter, Madeleine Malthête-Méliès.

In 1943, Henri Langlois hired Madeleine as a secretary at the French Cinematheque. After starting her job, Madeleine began to work diligently for her grandfather. In 1948, an exhibition entirely dedicated to her grandfather was organized.

I don’t have information about which films of Méliès were shown at the exhibition held in 1943. But the problem was that they didn’t have many films in their possession. Because almost all of Méliès’ films that have survived to this day were found after the 1950s. The stories of how they were found are entirely an adventure.

Movies Resurface

During his Chateau de’Orly days, people who visited him suggested that he should re-release his films, but Méliès couldn’t do so because he didn’t have the negatives. While contemplating, he remembered America. The negatives of his films should still be in America, but since Gaston passed away in 1915 and the shop there closed, he didn’t know what to do. However, Méliès was not the only one looking for these negatives; a man named Jean Le Roy was also on their trail.

Le Roy was the father of a friend to whom Gaston, thinking that Star Film’s films wouldn’t sell anyway, had entrusted the films. Le Roy sent Méliès a letter saying:

“A few years ago, I had the Star Film negatives in my basement.”

Upon learning this, Méliès asked Le Roy to place an ad in the newspaper. The negatives mentioned in the ad as stolen were, in fact, not stolen. Le Roy’s son had emptied the basement in 1921 and sold the negatives. A response to the ad came shortly after. The respondent was Leon Schlesinger, one of the producers of Looney Tunes. He had legally purchased 150 negatives of Méliès’ films. He even had a contract to show. Schlesinger, wanting to process and release these negatives, had failed, so he turned to other ventures. At one point, he even tried to sell the films to Paramount. Leon, who liked Méliès, made a deal with him and promised to share profits from potential copies. However, the sale did not happen because the theft ad Le Roy gave in the past negatively affected Leon.

Unfortunately, Méliès could never retrieve his films, but at least he lived knowing that Leon had placed them in a museum. Later, he wrote to him and said:

“A happy coincidence, much overdue, meant that the extraordinary productions of Georges Melies would not be lost forever.”

But the story actually begins anew here. As time passed, as people began to rummage through their warehouses, brand-new negatives started to emerge. In 1961, especially many damaged negatives belonging to Méliès were found.

In 1950, the Academy took over the negatives after Leon Schlesinger’s death. But by then, only 80 films remained. The worst part was that until 1958, the Academy didn’t even have an archive. Negatives were either damaged or decaying.

In the 1970s, archivist David Shepard transferred the negatives to the Library of Congress to show the films and wanted to restore them with new restoration techniques. But the negatives didn’t fit the machines; they even got damaged. Therefore, because a new technique was needed, the films returned to France. Or at least it was believed to have returned.

In 2016, employees accidentally found 80 negatives belonging to Méliès at the Library of Congress. It turned out that the newly found negatives were very high-quality and close to the original. Comparisons revealed that the films were indeed the original films. With this fantastic development, the Academy, LoC, CNC, and Lobster Film joined forces to restore the films using new-generation technology. In one aspect, we are lucky; if the films had not been found for a few more years, they would have become entirely unusable.

The restoration team, comparing the newly found negatives with the old ones, noticed a slight framing deviation in different negatives of the same film. Although the films were identical, there was a discrepancy in the frames. Some said Méliès had experimented with the first 3D shooting technique, but it was the difference between the American and French negatives. Thus, it was proven that Méliès had worked with two lenses simultaneously, sending them to Gaston.

Closing

Georges Méliès might be even more beloved today than during his famous era. He is the first name mentioned in all cinema history books after the Lumière brothers. The changing interests of the audience do not alter the fact that he was someone ahead of his time. As someone who has watched dozens of films from the past, I can say that many of them are quite dull. However, Méliès’ films still possess an energy, storytelling, set design, and experimental oddities that captivate, surprise, and enchant people even today.

Méliès laid the foundations of the cinema we love today with his imaginative creations. While everyone was capturing the daily life of the street, he brought dragons, devils, and fairies into his frame. He was the father of horror, science fiction, and the fantasy genre and the innovator of effects in cinema.

For me, Méliès represents not giving up on imagination at any age. When everyone is trying to act their age, Méliès said that what makes us who we are is what we experienced as children. Even in the melancholic times at the train station when he thought he was forgotten by everyone and that he had lost his films forever, he was still drawing his films and couldn’t forget the fairies on the stages of Théâtre du Châtelet and Théâtre de la Gaîté.

In times when telecommunication and visual communication were weak, many names, like Méliès, were forgotten. Buster Keaton is also one of those names. Today’s world offers us opportunities that were never owned before. Going back to the past has never been easier. We are even more informed about the past than those who lived in the past. In this modern age where we constantly move forward, what is the meaning of going back to the past? Because examining the past is crucial to understanding the future better and avoiding the same mistakes.

For this very reason, remembering Georges Méliès and what he produced is essential. It is my duty to remind us of who laid the foundations of the cinema we love today, the fantasies he created, and the experiences he had in his time, despite being forgotten and left in a corner. Remembering his legacy 85 years later and having the courage to write about his life is a source of pride for me.

Remember, if we love cinema today, it is because of Méliès.

Sources and Further Information

- Franju, Georges. ” Le Grand Méliès” (1952)

- Kaliç, Sabri. “Deneysel Sinemanın Kısa Tarihi,” Hil Yayınları (1992)

- Mény, Jacques. “The Magic of Méliès” (1997)

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey. “The Oxford History of World Cinema,” Oxford University Press (1999)

- Robb, Brian J.. “Silent Cinema,” Oldcastle Books (2007)

- Chansel, Dominique. “Europe On-Screen: Cinema and the Teaching of History,” Council of Europe (2010)

- Cousins, Mark. “The Story of Film: An Odyssey” (2011)

- Teksoy, Rekin. “Rekin Teksoy’un Sinema Tarihi,” Oğlak Yayınları (2014)

- George, Monty. “In memoriam: Madeleine Malthête-Méliès (1923-2018),” Domitor (2019)

- Lange, Eric. ” The Méliès Mystery” (2021)

- Solomon, Matthew. “Melies Boots,” University of Michigan Press (2022)